|

| The beautful, highly-developed Maltese coastline |

The country of Malta, where I lived during the summer of 2011, was a crowded place. On an area a bit

smaller than the Massachusetts islands of Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket combined lived 417,000 citizens, speaking their own language and with their own fierce culture. I lived in the hugely overdeveloped tourist district, the town of San Giljan (St. Julian's). Road ran directly along the perimeter of this whole northeastern coast, with hotels and "lidos" (beach clubs) every block, all more or less attached to each other the whole way. And lapping at the limestone just below the road or sometimes the tiny adjacent bedrock seashore was the blue, blue Mediterannean.

|

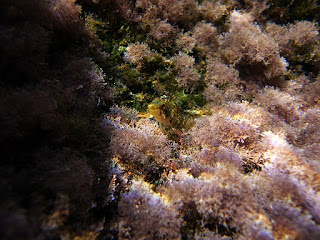

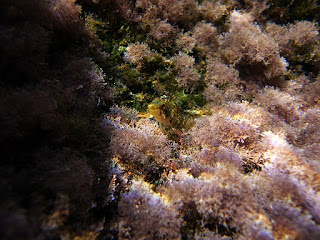

| Can you spot the goby amid the diverse algal forest? |

No rivers flow into the sea here, nor is the tiny island close enough to any continent for there to be significant coastal pollution. You can see into the water for perhaps 30 meters when you are not in a major population area, like where I was living, but even then you could see 10 meters deep! To celebrate the fact that our apartment was a mere hundred feet from the sea, which, as a marine biologist, I love, I jumped in every day. I would go for a run to get my exercise and really overheat myself so that I could stay in the sea longer. I carried my snorkeling gear in a bag on my back, and ran in my bathing suit! After the run, I'd walk down to my beach of choice (anywhere I hadn't yet explored along the coastal stretch), take off my shoes, put on my mask and snorkel, and jump in holding my house key! The water was warm in summer, 27 C / 80 F, so with the added heat of the run I could stay under comfortably for hours.

|

| Calmella cavolini, a Mediterranean aeolid nudibranch |

The benthic (i.e. bottom) habitat of the Mediterranean has no coral, but rather a forest of hundreds of different species of marine algae. These wild red, green, and brown multi-textured growths are kept neat and trim by dozens of species of herbivorous creatures, particularly sea breams, that snack on the algae every day. The resulting short, trimmed, underwater bonsai forests are thus the perfect habitats for me to hunt for the minute sea creatures that often bring so much wonder - nudibranchs, tectibranchs, pycnogonids, caprellids, harpacticoids, isopods, turbellarians! I'd search through them with glee, and occasionally find a creature I'd never spotted before. I'd run home to look it up, or bring it with me for a photo - giggling like a schoolgirl all the way, sometimes skipping dinner. (Although I would always return the creature where I found it.)

Some of my favorite creatures were the octopods. Yes, that is the plural of octopus. The octopus is more common in the Mediterranean than any other sea I'd been in. I can guarantee you an octopus while snorkeling right off the tourist beach. In tiny holes, cracks, and crevices, they occur every hundred feet or so underwater, watching the world. I used to love to interact with them. They all had unique personalities! I usually carry a single wooden chopstick with me to move around algae without having to use my fingers. The first time I came across an octopus while snorkeling after a run, it reached out of its cave and wrapped its tentacles around my chopstick! Surprisingly strong, the octopus wrestled the chopstick from my hands and I had to fight to get it back! Curious whether or not this was a common behavior, I approached an octopus I saw on another day with my chopstick, only to have it flee from its cave squirting ink at me as it jettisoned away! Yet another octopus lazily aimed its siphon at my hand and tried to blow the chopstick away from its lair with the jets of water pulsed out of its mantle.

Of course in every place where people live near the sea, there are people that love the sea. Some of my time in Malta was spent volunteering with a non-profit shark conservation organization, SharkLab Malta, a subsidiary of a UK group. With them I helped to lead snorkeling tours and collect data about sharks at the local fish market (at 3 am, an early business worldwide). As a trained PADI Rescue Diver with lots of research diving experience, I also joined in on coastal dive surveys to, well, look for unrecorded species around the island. We would go wherever we figured we'd find unique habitats, taking a tiny boat and SCUBA gear to sand patches, dropoffs,

Posidonia seagrass meadows, and submerged limestone caves. Among our many discoveries - which is what we call a trained mind attaching more importance to something than other observers - was the Bull Ray (

Pteromyleus bovinus), swimming in 20 feet of water over a sandy bottom off a popular beach. Though a Mediterranean species, it wasn't known from Maltese waters. Malta is an isolated island, so finding species there known from elsewhere in the Mediterranean still means a lot; it means they had to get there somehow, at some point in their ancestral history.

I met many good people in Malta, made many good friends, had a lot of adventures, made a lot of memories. The dives I have done there were magnificent. If you want to see Mediterranean marine life, stop by Malta. It's a magical little country!

Of course in every place where people live near the sea, there are people that love the sea. Some of my time in Malta was spent volunteering with a non-profit shark conservation organization, SharkLab Malta, a subsidiary of a UK group. With them I helped to lead snorkeling tours and collect data about sharks at the local fish market (at 3 am, an early business worldwide). As a trained PADI Rescue Diver with lots of research diving experience, I also joined in on coastal dive surveys to, well, look for unrecorded species around the island. We would go wherever we figured we'd find unique habitats, taking a tiny boat and SCUBA gear to sand patches, dropoffs, Posidonia seagrass meadows, and submerged limestone caves. Among our many discoveries - which is what we call a trained mind attaching more importance to something than other observers - was the Bull Ray (Pteromyleus bovinus), swimming in 20 feet of water over a sandy bottom off a popular beach. Though a Mediterranean species, it wasn't known from Maltese waters. Malta is an isolated island, so finding species there known from elsewhere in the Mediterranean still means a lot; it means they had to get there somehow, at some point in their ancestral history.

Of course in every place where people live near the sea, there are people that love the sea. Some of my time in Malta was spent volunteering with a non-profit shark conservation organization, SharkLab Malta, a subsidiary of a UK group. With them I helped to lead snorkeling tours and collect data about sharks at the local fish market (at 3 am, an early business worldwide). As a trained PADI Rescue Diver with lots of research diving experience, I also joined in on coastal dive surveys to, well, look for unrecorded species around the island. We would go wherever we figured we'd find unique habitats, taking a tiny boat and SCUBA gear to sand patches, dropoffs, Posidonia seagrass meadows, and submerged limestone caves. Among our many discoveries - which is what we call a trained mind attaching more importance to something than other observers - was the Bull Ray (Pteromyleus bovinus), swimming in 20 feet of water over a sandy bottom off a popular beach. Though a Mediterranean species, it wasn't known from Maltese waters. Malta is an isolated island, so finding species there known from elsewhere in the Mediterranean still means a lot; it means they had to get there somehow, at some point in their ancestral history.