|

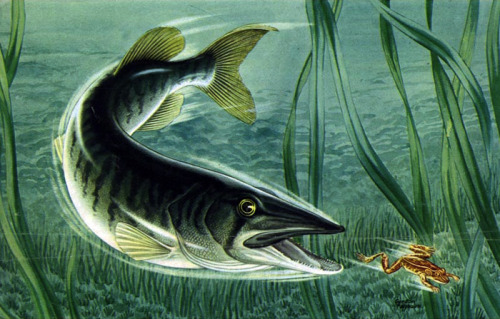

| The chain pickerel, Esox niger |

9. Pickerel are from the family Esocidae, called pike-fish by the English because they are long and pointy like the eponymous weapon! There are five species from the family Esocidae from the eastern USA and Canada. One species, the Northern Pike (Esox lucius), also naturally occurs in Eurasia - one of the few freshwater species to occur naturally on different continents!

8. In Canada, "pickerel" refers to Sander vitreus, a species we call walleye, or wall-eyed pike. Of course, both names are misleading because Sander vitreus is simply not a pike (i.e. not a member of the family Esocidae)! Thus, the problem of common names!

|

| In reality, a frog would rarely see this grass pickerel coming. |

6. Pickerel survive icy northern winters by moving from shallow weedy areas to deep waters that won't freeze over. Because their metabolism slows down, a pickerel that might normally need to feed every day can last nearly two weeks without a meal in winter!

|

| Now THIS would be a team... The Boston Esox. |

4. A "Tiger Muskie" is a cross between two pickerel sister species - the Northern Pike and a Muskellunge (Esox masquinongy, from the Algonquian tribes' words for "great pike-fish," or "ugly pike-fish"). Like most hybrid species, they are infertile. This means that wherever they occur naturally, they are not members of a long, proud line of pure heritage, but rather the beautiful offspring of chance passion between distinctly different parents. Were they confused, these parents? Lame creatures, merely misled, fooled by each other? Or were they passionate risk takers, chasing a biologically forbidden love?

|

| Taking species management in our own hands (Esox lucius) |

(baby tiger muskie pic)

2. The larger Esox (pikes and muskies) are not native to Massachusetts. In 1950, hundreds of 12+ inch northern pike adults were brought up from Lake Champlain in New York and released around Berkshire country in that year in hopes of establishing reproducing populations, mostly for sport. I wonder what it was like to drive that payload!

.

.

and of course....

.

.

.

.

wait for it...

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

1. PICKEREL ARE SO CUTE!