"BRUUURP.... BRUUURP.... BROH-UHRP!"

A tall, dark-haired 40-something Tico farmer creeps into foliage, listening.

"BRUUURP.... BRUUURP.... BROH-UHRP," he calls again for a creature of the night, waiting. He whispers to me while gazing into the foliage, "He's close...."

Suddenly, a brave little "broh-uhrp" chirps back from behind some banana leaves. Our farmer, who doubles as a wildlife guide, moves swiftly. My travel buddy and I peer into the thick green. Where did he go? We've only just met this man, with whom we'd organized a nighttime nature walk after arriving tired to our hostel in La Fortuna, Costa Rica. In the less than ten minutes we've known him, we've lost him in some overgrown bushes aside a soccer field. We were feeling worried, apprehensive, and skeptical of this guy, our arms crossed and our eyes peering into the leaves, when he appeared behind us.

|

| A startled Red-Eyed Tree Frog (Agalychnis callidryas) |

"Here, get a picture," our guide said, as a Red-Eyed Tree Frog,

Agalychnis callidryas, crawled off a held stick and onto a banana leaf. We were stunned. And then my camera shutter started clicking. The stare from this beautiful Central American endemic, a popular and immediately recognizable

symbol for rainforest conservation, dredged up childhood memories of rainforest dreaming. Bright, orange feet, blue flanks and legs, and red eyes dazzled us, which is what they're meant to do. See, the frog covers all these colors up when sitting on a leaf; it sits on its orange feet, it pulls its legs against its body, and it closes green eyelids. When resting, it appears to be a green blob. Should a predator investigate the green blob, the non-poisonous frog resorts to its "startle coloration" for defense - the frog opens its eyes, flashing the enemy with color before making an escape. This potentially freaks out their predators. Of course, that means great photos for us crazy nature tourists! Sure, flash me, frog - better for the camera! They can live to 5 years, and will vocalize to attract mates or warn off other males (competition is intense - males get a free ride on the female's back during mating). It was one of these brave males that fell for our guide's deception, countering with its own defiant "broh-uhrp." It was the defiant "broh-uhrp" rebuttal that solidified Geovani Bogarín's legitimacy as a fantastic wildlife guide that night.

|

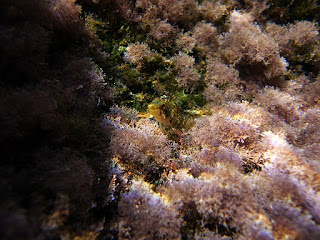

| A terebellid flatworm navigates the fungal forest under a log |

You can learn about Sr. Bogarín's 20 year history as a wildlife guide in La Fortuna from

the New York Times article written about him in 2008. I'd rather share what the article glossed over - his respect for all species. You see, a person doesn't "memorize" 850 species of birds, as the Times author wrote - or 50 species of frogs, or hundreds of species of trees, orchids, and mosses - in the same way that you don't "memorize" the names of your family and friends. You know their names because they play a role in your life; you see them and interact with them, laugh and cry with them, perhaps share a meal with them. I understand this, too; from all my time underwater in the Red Sea I have "memorized" hundreds of fish, crab, snail, slug, and worm species that were part of my life then. Geovani knows these birds, lizards, frogs, ants, and bats because he lives in the forest and pays attention to it. His "house" is just a wooden deck supported ten feet off the forest floor by large posts. Corrugated steel acts as a roof to keep out the rainforest's eponymous weather. A propane camping stove rests on a table in one corner - the kitchen. A hammock is stretched between two supporting posts on the other end - the bedroom. He leaves bananas out for the raccoons that like to visit sometimes. And at night, he rocks in his hammock and listens.

|

| Blue-jeans frogs Oophaga pumilio secrete unpalatable toxins |

For the past 10 years, Geovani has been developing a trail through that parcel of jungle right off the main street in La Fortuna. Here he challenges his ecotourists, "make a list; what species do you want to see?" He's calling it the "Parque Natural Los Niños," and 20 years of wildlife guiding means he knows what we want to see, and that he can find it among these trees. "So many people come here and they don't see what they're looking for - I heard about some German girls a few days ago who paid $65 for a wildlife hike and they didn't even get to see a sloth," Geovani said, shaking his head. (The sloth, "oso perezoso," literally translated to "lazy bear," is one of the most well-known residents of Costa Rican forest life - just look high up in the

Cecropia trees and you'll see one sooner or later!) Of course, Geovani's observation can be interpreted a few ways - the larger, federally-sponsored national parks where most wildlife tours are conducted have high standards, more land to maintain, and more stakeholders to please, services which all must be paid for. And you can't guarantee wildlife sightings, right?

|

| A large brown spider (Sparassidae?) camping out on bananas |

But with his comment, I see Geovani shares my lament - while many have become acquainted with nature, few understand it. With understanding comes guarantees for cool creature spotting. Nature is a system; except for modern humans, all life obeys rhythms. The annual shift in the angle of the sun's rays on Earth lead to weather (wind, evaporation, rain) and seasonality, which control the abundance of various plants. These factors act with others, like the phases of the moon, to trigger significant events in the lives of animals and support their growth. When frogs give birth, for example. Or when dragonflies take flight. Or how many larval instars of huntsman spiders will survive until adulthood. Or if the mot-mots or oropendulos will decide there is enough food or absent predators to justify leaving for the annual migration to a low-valley avocado tree instead of a high fern in the cloud forest. When we lived in nature, as a human species, we noticed such cycles and made decisions using them as well - they told us about our surroundings, about the weather, about our food. Sure, today Geovani's understanding of the call of a lusty frog or the location of a mother sloth with child brings him direct monetary income - and indeed perhaps the only way to understand so deeply is to make it your full-time job - but in the past these things would have been the pulse of our friend, the forest, the land we live on.

|

| Polydesmid millipedes may excrete cyanide to deter predators! |

As Geovani and I discussed these truths, as we lamented modern society's ignorance or apathy towards the one "philosophy" that has the power to support humanity because it provides food and shelter just by existing, my travel buddy watched the fireflies blink on and off in haphazard loops, merely awaiting the moment when the hippie talk would end and the newfound camaraderie would be celebrated with beer. After all, our modern society runs on lawyers and iPhones and barbie dolls and Burger King, and we are products of our upbringing - beer was surely forthcoming (for those of age)! But it is these rare glimmers of mutual understanding I occasionally find in random others that remind and confirm to me that I am a member of the human species, a creature with a role and a long history in this system.

|

| An insect undeterred by millipede defenses! |

If you go to La Fortuna and want to hang with Geovani Bogarín, try calling him at 86269348, or just ask any of the locals. They all know him, and really seem to like him, too.